Hello and Welcome. Today’s chapter is on the Reformation and the Counter-reformation, which, as expected for most religious conflicts, has very little to do with religion and more to do with the way that people in power use their power.

To explain the reformation, I cite Britannica, “the resulting intrigues and political manipulations, combined with the church’s increasing power and wealth, contributed to the bankrupting of the church as a spiritual force.” [1] This power and wealth came from the tax that all Western European countries had to pay to the Catholic church.

Tax is and has always been a complicated thing. People hate it and it makes people hate the government. In the past, taxes were made on whatever seemed taxable. For taxes on landowners, for example, a tax collector would show up, look around and assume what would be a reasonable tax, and request payment. For the church, there was the added factor that it was a religious matter and not a governmental matter, so avoiding the tax to the church could be considered immoral and therefore necessary for the tax to be paid. It seems to be that the catholic church, for example, requested 10 percent of a person’s income, but I didn’t verify this past Wikipedia. [2]

So, when the people saw that the clergy was living lavishly and their training and requirements were not standardized, this was an insult to the layman. The Council of Trent, a move by the catholic church to address the needed reform of the church as they noticed it internally and from the pressure of the lay people, was meant to respond, “emphatically to the issues at hand and enacted the formal Roman Catholic reply to the doctrinal challenges of the Protestant Reformation.” [3]

It addressed these issues, along with addressing the issue of corruption amongst the clergy, and issues of marriage in the clergy, which was, properly not allowed. It also required actual and regulated training across every diocese and required that bishops actually preached. Luxurious living by the clergy was curtailed, and the clergy was forced to live within their diocese, nepotism was forbidden, and mass and liturgical music was standardized. [4] This happened for several years, so I very likely did not cover all of it.

On the other hand for the reformation, Russell says, “Their theology was such as to diminish the power of the Church”[5] Which was accomplished by banning indulgences, the buying of apologies for God so that he may perhaps reduce your time in purgatory, and got rid of the idea of purgatory as well. Because of the reduced power of the church, now that it could not collect taxes and their ability to moralize gone since they could not excommunicate, heads of state effectively wielded more power.

This power struggle between religion and kings is best exemplified by Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, who was excommunicated after he deposed the Pope in 1076, who thought he couldn’t do that, and due to revolt in his lands because of the excommunication, had to walk to Canossa to apologize to the pope, whereupon the excommunication was lifted, thus asserting the power of the pope over the Holy Roman Emperor.

Because the Church tax and the power of the catholic church were missing from these largely protestant countries, the Kings could essentially step in and take over the control of the church. Martin Luther, a nominal leader of the Reformation, would “wherever the prince was Protestant, to recognize him as the head of the church in his own country”, which “accelerated the already existing tendency to increase the power of the kings.” [6]

What does Philosophy have anything to do with this? People really didn’t like heretics, and the Catholics considered the protestant heretics, and the protestants might as well consider the catholic heretics, even though their issue was mostly with the church. Nonetheless, the church does not fight wars, but people do, and, “Gradually weariness resulting from the wars of religion led to the growth of belief in religious toleration, which was one of the sources of the movement which developed into eighteenth- and nineteenth- century liberalism.”[7]

Not only that, but the Jesuits, whose purpose was the enforcement the outcomes of the Council of Trent, were practically militant, and since their founder, St. Ignatius of Loyola was “a soldier, and his order was founded on military models; there must be unquestioning obedience to the General, and every Jesuit was to consider himself engaged in warfare against heresy.”[8]

Little fun fact, the leader of the Jesuits is nicknamed Black Pope. Anyways, they spread their missionaries far and wide, who were especially devoted to their craft of converting, and were “concentrated on education, and thus acquired a firm hold on the minds of the young. Whenever theology did not interfere, the education they gave was the best obtainable.”[9] This is the reason why Jesuit schools have typically a high reputation for being pretty good at educating, compared to their public counterpart.

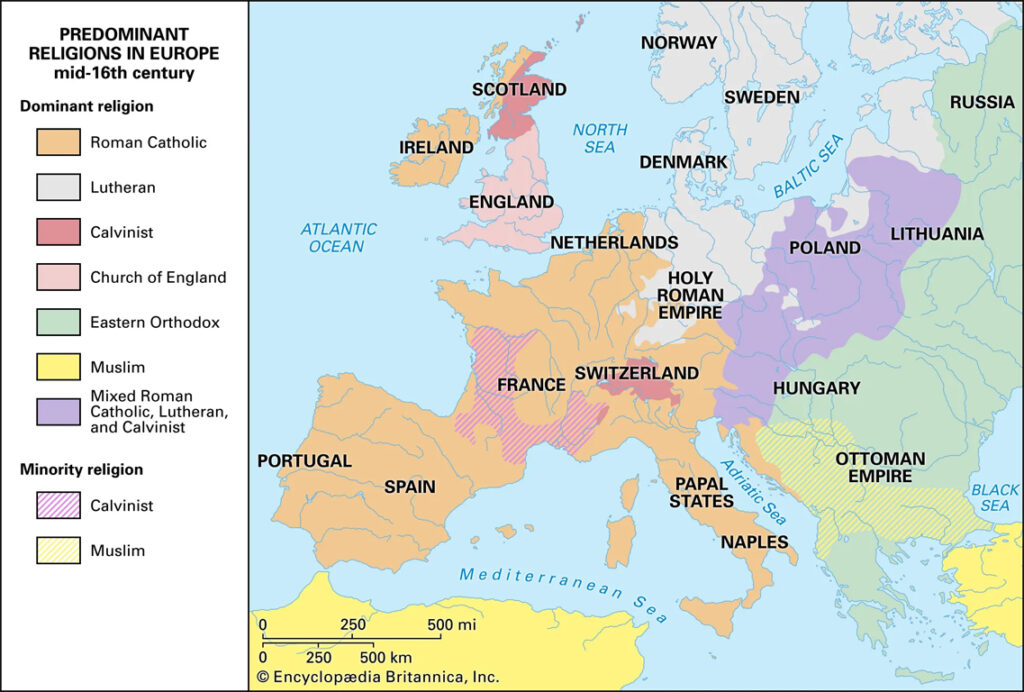

The Counter-Reformation was effective in northern Europe for the most part. England went their own way in their religion and so did northern Germany, but parts of southern Germany like Austria and Bavaria returned to the catholic fold. France, which for a time allowed a level of toleration through the Edict of Nantes, eventually reneged on this and revoked the edict. Across the Catholic world, generally, the church stopped being so bad, or at least less bad compared to what they were doing before. At least now it was standardized.

Because Universal Christian unity now seemed impossible or undesirable in the wake of the religious wars, this ideal was abandoned and it “increased men’s freedoms to think for themselves, even about fundamentals.” [10] Further along, he also says “Disgust with theological warfare turned the attention of abled men increasingly to secular learning, especially mathematics and science. These are among the reasons for the fact that, while the sixteenth century, after the rise of Luther, is philosophically barren, the seventeenth contains the greatest names and marks the most notable advance since Greek times.” [11]

And with that, I leave the religious matters and move on to philosophers and philosophy, for the rest of the book, where seemingly nothing is titled or based around religion, thankfully. Before I continue, some due diligence as well. Russel’s book is critiqued for his coverage after the 15th century for being oversimplified and missing core parts of the philosophies he covers. So, I will try to pull in from other sources to fill this gap. Mainly this will be from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which provides reference articles written by many scholars around the world on philosophers they specialize in, who will give more nuanced views on the issues, and who will address what parts of these philosophers are still worthy of discussion today and which parts are largely abandoned for better thinkers.

Next week, we will look at the rise of science, covering I believe, the thinkers that defined modern science, and the following week moving on to Francis Bacon, the father of the scientific method.

Citations

“Counter-Reformation | Definition, Summary, Outcomes, Jesuits, Facts, & Significance | Britannica.” Accessed July 29, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/event/Counter-Reformation.

“Reformation | Definition, History, Summary, Reformers, & Facts | Britannica.” Accessed July 29, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/event/Reformation.

Russell, Bertrand. A History of Western Philosophy. A Touchstone Book. New York u.a: Simon and Schuster, 1972.

“Tithe.” In Wikipedia, June 27, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tithe&oldid=1162204535.

[1] “Reformation | Definition, History, Summary, Reformers, & Facts | Britannica.”

[2] “Tithe.”

[3] “Counter-Reformation | Definition, Summary, Outcomes, Jesuits, Facts, & Significance | Britannica.”

[4] “Counter-Reformation | Definition, Summary, Outcomes, Jesuits, Facts, & Significance | Britannica.”

[5] Russell, A History of Western Philosophy. (523).

[6] Russell. (p. 523)

[7] Russell. (p. 524)

[8] Russell. (p. 524)

[9] Russell. (p. 524)

[10] Russell. (p. 525)

[11] Russell. (p. 525)