Chapter III. Machiavelli

Machiavelli (1469–1527) was the pre-eminent political philosopher of the Italian Renaissance. What I appreciate most about Machiavelli is not the political philosophy in particular, but rather the honesty that comes with his writings.

Russell says of Machiavelli’s readers: “It is the custom to be shocked by him, and he certainly is sometimes shocking. But many other men would be equally so if they were equally free from humbug.”[1] Humbug, meaning: “something designed to deceive and mislead” or of a person, “willfully false, deceptive or insincere person.”[2] Let’s take a detour into talking about deception to make a point about the “humbug” attitude.

Humbug and Deception

Say your mother looks and says to you “The trash is full.” The implication almost always means for you to take out the trash. In this position, she doesn’t have to thank you, or even necessarily acknowledge that you did anything. She uses social and familial hierarchical pressure, so to speak, to make you take out the trash. She could also ask, “Can you take out the trash?” and now your heart may be set on a mission where intentions and rewards are clear. You say, “Yes, I can… done!” and she responds, “Thanks!”

Even though the effort was physically the same, the mental effort was much less. You don’t have to question whether she is actually asking you to take out the trash, and you know that she is thankful to you. Compare this to the former, and there may be no reason for thanks if it wasn’t directly asked, and for whatever reason they don’t feel the need to give thanks, nor do you feel thanked, since this might be something that is “expected to be done.”

Nonetheless, when your mother asks you to take out the trash, it is not really a choice per se, but an expectation at the very least and at most, essentially a command. Despite the social pressure to do the task, you feel that you are making your own choice, and you have the right to say yes or no, but in reality, there is heavy pressure for you to say yes and consequences for saying no.

In the cases of peer pressure for example, sometimes coming from the nicest of people, you will naturally feel shame or cowardice even if your friends say, “You don’t have to do it.” This is because it is presented as a challenge, and backing down would amount to being less than what is expected of you.

Peer pressure has already happened before they clarify that you don’t have to, because either consciously or subconsciously they acknowledge that they are putting you in a situation that you are uncomfortable deciding on, otherwise, why would they clarify that you have a choice? It isn’t really about whether someone has the ability to always decline peer pressure, but rather why would you put someone in a position to have to stress over the choice in the first place?

In both cases, there is a dynamic of social pressure that weighs on your choice to say yes or no, whether they superficially clear the air about whether you have the choice to say yes or no since no implies shame and yes implies social conformity and appeasement.

Let’s make the case of two equal partners in a relationship who alternate in taking out the trash. There is an equal expectation for both individuals to take out the trash. If both have created space and comfort for the other to share and agree or disagree, one could say “You take out the trash today right?”, the other could say, “My back hurts/I’m tired/sorry I’ll handle it next time can you do it this time?”

While there is normally social pressure for the person to be responsible for their duties, this pressure is eliminated because of the trust between the two and the belief in the excuse and that the agreement will be fulfilled the following time around.

Between a group of friends who do not hold expectations from one another, and where they feel comfortable with one another, a challenge in the form of peer pressure would not really amount to peer pressure – just a simple challenge you can attempt or decline. If you fail, you feel sure that they are laughing with you, and not at you, and the idea of shame never crosses your mind.

It may also be the case that you are not authentic to yourself, so you hold an image of yourself that isn’t you in your mind to which you pose the challenges of peer pressure, which isn’t congruent to the feeling that your body is expressing, a discomfort with the challenge. You are acting beyond yourself and this will eventually result in burnout of some kind.

To protect yourself and your friendships, be more honest about whether you want to do something or not. What could happen otherwise is resentment towards yourself and other people.

Imagine that a person loves going bowling and you believe that you are indifferent about the activity when really, you’d prefer to do something else. Over time, you don’t refuse the requests to go bowling and eventually begin to feel pressured to accept the requests of bowling after going several times and a trend you’ve set of appearing interested.

Imagine later on that you become tired of having to put up with pretending to like bowling, either because you realized that you did not like it at all in the first place or you were repressing your feelings of boredom. Eventually, this will blow up in the face of the bowling fan and friend, who feels they have been deceived in some way about your interest in the manner when suddenly you never feel like going bowling again.

Why not be forward about your thoughts in the first place? Forwardness is oftentimes frowned upon, and our meaningful social interactions are shrouded in subterfuge. We are too embarrassed to be forward with one another, so we ask peripheral questions to find out and get what we want. I do think that there is some worthwhile and fun interaction even when this does happen, but some people use this posture in all circumstances, which necessarily becomes terribly confusing after some time.

Some of the most repulsive feelings I have towards people is when I feel that someone feels forced to interact with me due to circumstance. Say I am at a public gathering with many mutuals around. Because of a shifting of people left and right, I find myself next to a person who is a mutual or acquaintance, and they are no longer talking to someone, and I am not talking to anyone either and we happen to be next to each other. They say,

“Hi how are you doing” sheepishly, and I think Shoo! opportunist… and say,

“Hey, what’s up”,

“It’s nice to meet ya”,

How can you possibly know whether it will be nice to meet me yet? “Likewise,”, I say, and so on goes the empty conversation.

I have a hard time maintaining this sort of conversation because I feel used, and I genuinely enjoy having conversations, but certainly not empty vapid ones. It is difficult for me to say “I don’t care to be your entertainment right now”; I am certain that I am not a jester you can turn to when all of your other friends are no longer paying attention to you. But if I am curt and dry, then I have disrupted the social pleasantries and I have betrayed the general societal humbug.

Although deception is part of our normal routine in interaction, we don’t like to admit it. Russell says of the general disdain for Machiavelli that “Much of the conventional obloquy that attaches to his name is due to the indignation of hypocrites who hate the frank avowal of evil-doing.”[3] This would be because breaking the social norms and the deceit that we engage in to maintain “normalcy” is dangerous for social cohesion. If I were to not respond to the conversation forced upon me, I would naturally appear as the bad person, and generally, this would not be a bad assumption.

Say that there is a person who constantly breaks social norms. We would be right to be wary of them perhaps because we imagine that they might have a propensity for murder, and we wouldn’t be surprised if they turned out to be a psychopath. For the most part, when social norms are broken, there is no discrimination between the most important norms being broken and the minor ones; the person breaking these norms will amount to a general intuition within us of being “weird” and we will treat them as such, with the appropriate caution.

We could avoid this logical leap if we were just more honest in our behaviors and appearance. When I walk here or there. I try not to worry as much about the appearance of the stupid side tasks that I like doing as I walk places. Sometimes I’ll whirl my pocket watch around my finger, other times I flip a coin in my hand as I walk. Both of these are satisfying, but I haven’t decided to begin skipping yet, despite it being pretty fun and faster than walking places.

Florence During Machiavelli’s Time

What inspires all of this is the way that Machiavelli built trust and expectation by laying out the realistic desires and outcomes of each party involved so as to form a detailed chain of cause and effect that is reliable in itself based on the interest of each party, which can be built partially with history and the study of the way people have worked under similar circumstances. Thankfully for Machiavelli, it was the Renaissance, so he has a long list of historians who are newly studied and valued to pull from to build his ideas.

The Prince, His most well-known work, “was written in 1513, and dedicated to Lorenzo the Magnificent, since he hoped (vainly, as it proved) to win the favour of the Medici”. [4] Although Lorenzo died in 1492, he was a magnate and incredibly important for the development of Florence until his death and the religious takeover.

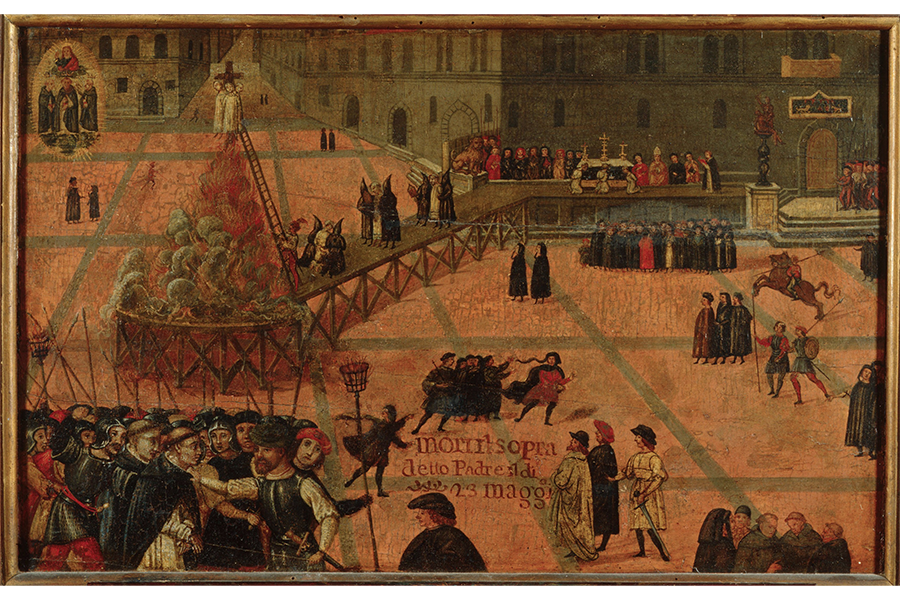

Florence in the late 15th century experienced a brief revolution under the rule of Savonarola. A more unhinged Martin Luther, who instead of nailing 95 theses to a church door, decided to overtake the government, and attempted religious reform, and burned a bunch of vanity items, an event called the bonfire of the vanities.[5]

The bonfire of the vanities (1497) burned any cultural object that was anti-his-idea-of-church. Eventually, he was excommunicated for not joining the catholic league (a coalition of minor Italian states organized by the pope) against French invaders, whose presence was the very reason for the instability of the Florentine government which allowed him to take power and later on burn countless cultural objects for religious ideals.

His holy qualifications were questioned since he was excommunicated by the pope a year earlier and he was generally losing favor with the people. A rival Florentine preacher called him out because Savonarola hinted at divine guidance for his prophecies and preaching. A trial by fire – walking through coals – was to be the test for Savonarola, since if he really was divinely guided, God would intervene.

He could not really back down from this challenge without public outrage since his prophecies were being doubted, and the pope was going to impose further sanctions on him and therefore the city of Florence.

Some other guy volunteered to be his champion, and they got really nervous about walking on coals. They stalled so long (hours) that a sudden rain quenched the coals and the crowd got upset because the burden of proof had been on Savonarola to show his divine guidance.

The crowd dispersed, and Savonarola went home, A mob stormed the convent where he stayed, Savonarola and two others were imprisoned, and he was tortured and confessed that he made all of his prophecies up, then burned at the stake.

Machiavelli saw all of this; the rise of a theocratic ruler whose authority depends on the belief of the people rather than the actual and wielded power of a prince. Which would be found in popularity, fear, wealth, armies, and the maneuvering of these and other medieval-esque powers. When the Medici returned in 1512, (Savonarola died in 1498, and the government was unchanged until 1512), Machiavelli used this opportunity to win the favor of the new Medici ruler.

If Savonarola was evidence for anything, it was that relying fully on religion as a basis for power was not tenable, and he needed to pursue other means of power to maintain his position in the government.

The Prince is essentially a dumb idiot’s guide to ruling a country, a handbook for the Medici to use to keep and maintain power, “The Prince is concerned to discover, from history and from contemporary events, how principalities are won, how they are held, and how they are lost.”[6] Machiavelli was one of the first to use history as a basis for analyzing current events to see what the expected outcomes are.

Religion, for example, was for Machiavelli a glue to hold society together, rather than a factuality whose moral imperatives must be followed: “He holds that religion should have a prominent place in the State, not on the ground of its truth, but as a social cement: the Romans were right to pretend to believe in auguries, and to punish those who disregarded them”[7], and a little later Russell says “We learn that they should keep faith when it pays to do so, but not otherwise.”[8]

The idea of an objective perspective of truth is questionable, people have their religions, and they all have a particular perspective on the nature of the world. This includes moral truth, since morals do not spring from within us, but are understood in society implicitly as we grow up and are rewarded and punished for certain acts which are viewed as right or wrong based on religious and cultural context, which are strongly tied together.

A conscience is something that is developed as we live in the world; notice that most of us do not care in the slightest about whether animals are being mass farmed for consumption, despite our feelings when we see a cute cow prancing through a grassy field because this is not our typical encounter with cows

Similarly, I can agree to chickens being mass farmed in whatever way doesn’t eventually kill me (considerations for climate change and safety of food for consumption are present in this valuation) as long as I understand the possible implications of animal ethics, how other people might feel about animals, and the social consequences of consumption and anything else you can possibly imagine as mattering. But we tend to not be exposed to this kind of thinking, except for when it shows up in documentaries like Super-size Me which dramatizes the situation.

Notice for example, that we do not eat dogs despite them being effectively the same as any other farm animal. This is simply because of the arbitrary feeling we have developed toward pets as companions. Thus, our ethics are contextual to the society, and the religious context that society was brought up in. With the absence of religion in our societies, the question of where morality comes from is hotly debated.

Our feeling of wanting to avoid eating dog meat is the same effect as being socially aware of whether your friend has the capacity to decline or accept shots of tequila knowing the social pressure before you breach the proposition of taking shots. You know that if you ate a dog you would feel social shame, and you know that if they declined the shot of tequila, they could feel social shame because of the social context

We have to hold trust and expectations for each other for requests to make ethical sense. I have absolutely no expectation that the random person at a random location turning to me to speak is going to maintain any sort of interest in me after the moment has passed, and it doesn’t make any sense to me to invest any time or energy into this sort of conversation, and at worst it is disrespectful to my personhood to treat me as much.

To reiterate, despite the ideas we have of morality being artificial, they are entirely real in so far as we feel them to be real, and we should treat them and understand them as such. The importance of this belief is the basis for regular human interaction and development, but at the same time, we have to actively think about those that are purely puritanical and possibly detrimental and consider whether we want to maintain them.

Confidence in Consistency

The pre-Christian Romans held a polytheistic religion allowing people to choose and worship whatever god they pleased as long as they believed in the gods in the first place. Later on, during the imperial period, they necessarily had to believe and pay tribute to the imperial cult or face punishment. The imperial cult was the deified emperors of Rome and thus served as a proxy to show fealty to the imperial government.

Today, Church and State are separated, which is undeniably good for the well-being of a state. The state cannot be undermined by religious events or requirements, but what was important for Machiavelli was not the belief, but at the very least pretending to believe. Christianity was so successful with the legions and people of Rome because it provided relief and an answer to the constant invasions and undermining of safety which was brought by the “barbarians” raiding and destroying the sense of safety in the world.

This belief in Christianity maintained some social cohesion at a time when the Roman imperial government was undermined by constant invasions and civil wars.

What is important about religion is that it provides confidence. A feeling that there is cohesion to the world and therefore the worst moments being relieved by a sense of safety or expectation with respect to God.

God, in our modern secular context, is still a very useful concept because we hold otherworldly expectations of the experienced world around us that we truly believe with no reason to do so.

I will provide two examples. If you are crossing a sidewalk, you have no good and guaranteed reason to believe that someone will not snap and run you over. A person in a vehicle is making an active decision to hold their foot on the brake pedal. They make this decision because of the punishment of crime, a play between desires and feasibility, and importantly that we place moral and therefore religious value onto the life of other people.

If you are having a conversation, you meet someone new, they have no reason not to lie to you about everything to get what they want. What guarantees their truthfulness? A general conscious attitude we hold towards liars, that is internalized within all of us (hopefully) that prevents us from fragrantly lying about everything. This is something that comes from practicality and religion – Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

As for practicality, We may actively work against whatever desire by presenting ourselves as truthful depending on the specific circumstance, but we must also keep in mind that once someone catches you lying once, your ability to maneuver around this person for whatever you need is reduced significantly. They will always assume that you are lying after that incident.

If you are caught lying, you have to provide them with more of a Machiavellian analysis of what it is that you need or want, why they should trust you, what they gain, and perhaps why what you need is also in their interest. There is some practical purpose in not lying, but the belief that people are not lying now, and later in the future is mostly a spiritual sort of belief.

Some Philosophies nowadays hold that the effect of religion – now that a proper one is absent – is maintained by the strict manners and ways of being that we maintain in our societies through shame and aggrandizement. The big Other, a Lacanian term, relates the idea of the meaning of action to the imaginary other we maintain as an amalgamation of social expectations formed throughout our life.

This view of religion that Machiavelli holds is an excellent place to begin understanding his other positions when it comes to politics. Religion, being one of the most dangerous topics to discuss liberally – because of the risk of excommunication – was nonetheless a tool for Machiavelli to make available to the Medici, at the very least before it fell off in power with the Enlightenment.

Purely from a catholic perspective, to use Christianity in this way is morally bankrupt, but once again, morals are not an objective fact of the world because they stem from religion, and we haven’t settled on which one is the right one since Earth as a population is still shifting what it believes in.

Which means for what end?

Russell says, “The Prince is very explicit in repudiating received morality where the conduct of rulers is concerned. A ruler will perish if he is always good; he must be as cunning as a fox and as fierce as a lion.”[9]

From his perspective, the most important aspect of a ruler is the ability to maintain power, whether it be exploiting religion, assassinating rivals, undermining opposition through propaganda, or being both popular and feared. Otherwise, whatever aims you had in mind become impossible. And if you hold these end aims to be a good thing, why not pursue them with any means?

Let us quickly circumvent objections to this: if your means undermine the end in any way, then obviously the means are not worthwhile. So if your means to peace on earth is to kill all people on earth, while it certainly brought peace to earth, the means did not respect the caveats of the end which are not obviously present. Peace on earth clearly refers to peace on earth for humans. Keep in mind that a good means to an end would consider all of the implications of the end and the means to find the correct course of action

The means of action are good or bad with respect to what? Typically, it tends to the virtue, which is inherently a religious proposition. If a person lives their life unethically but ultimately ends up happy and fulfilled and successful in life, what is the comeuppance? Jeff Bezos started Amazon and the morals of its operation are questionable at best.

Nonetheless, if he is happy, then his means were perfectly adequate for himself. Is his conscience, ok? Maybe he believes in pulling oneself up by their bootstrap, so he feels as if he gives the world a lot of opportunities in terms of jobs, for example. But if he feels guilty or worries about what others think of his actions, then his means were not adequate to his ends since his sadness over his public perception would haunt him forever if his desire was to be happy.

If his desire was accruing as much money as possible while exploiting the most people, then great success! He has nothing to worry about his means unless his means are undermined by other people in this society, as they are now, and he has to consider readjusting to alleviate pressure from people trying to prevent his end goal, whatever it may be. So it seems that being a ruthless CEO forcing people to work in below-average conditions is likely not sustainable and he’s better off paying a slightly higher premium on employment or working conditions for continued business operations.

Consider that if the early industrialists had been more chill about their use of child labor and had better working conditions then it is entirely possible that we could still have child labor.

The Conquistadors and missionaries of the 16th century believed they were on a mission sent by God to convert the peoples of the new world – I am sure some of them died fully content and glad about the means they used to achieve their end, to evangelize.

What is the limit on any path of action? Relative to the end, “It is futile to pursue a political purpose by methods that are bound to fail; if the end is held good, we must choose means adequate to its achievement.”[10] History is written by whoever is left over and has some power. Morals, as a product of society, will therefore eventually justify past acts in a historical canon that makes sense to us.

The new world is entirely Christian, and if the Conquistadors truly believed that it was god’s will to spread the gospel to the new world, they triumphed. Not only that but if their religion is right, they saved millions of people from straying away from God’s word. Wouldn’t we wish there was someone who prevented their vicious and inhumane actions? There was! Unfortunately, he was powerless and unsuccessful.

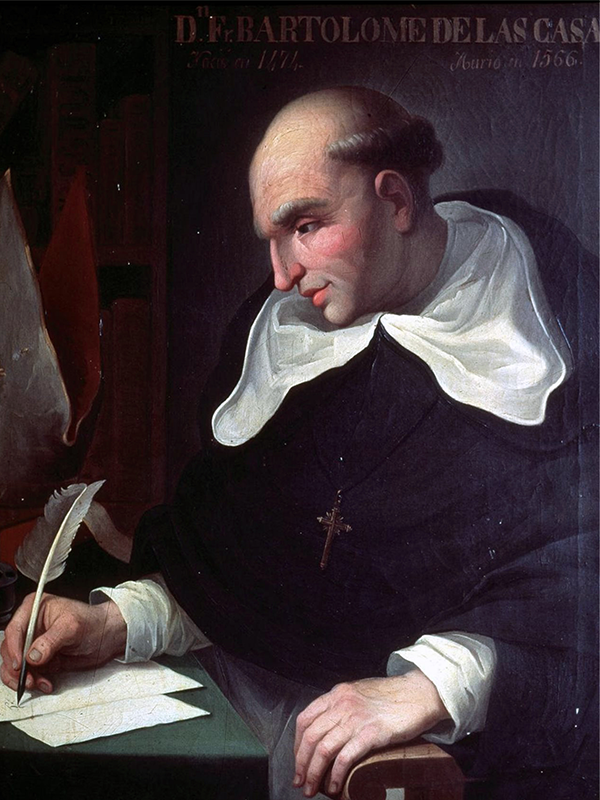

Bartolomé de las Casas was a “16th-century Spanish landowner, friar, priest, and bishop, famed as a historian and social reformer,”[11] who largely failed in preventing any of the atrocities committed upon the natives of the new world.

Despite his lifetime of advocacy for the native peoples and his disavowal of their treatment, the encomienda system, a system where the Spanish crown granted Spaniards land and natives, and the Spaniards would be responsible for paying, protecting, and converting the people. Instead, the Spaniards did not pay, and killed, and forcibly converted the people. His simple moral attacks were not enough to sway the moral understanding of the status of native peoples as more than cattle in the Spanish government.

You could say that he could’ve worked through the system and then gathered enough power and backing from other prominent Spaniards to mount a more effective attack and reform the particular form of colonizing brought by the Spanish by undermining the power of the crown by agreeing to any new request by the king only if he compromises with De Las Casas and his provisions for the treatment of the natives.

For whatever reason, this did not happen. The native peoples do not get to experience his virtuous attempts of spoken argument but rather the success of the encomienda system as his moral attacks drag on with no effective change in the lived experience of the native peoples.

He sought an audience with the King, something which seems to take a long time before eventually, the King died without ever having the meeting. He could’ve instead strong-armed the king with unrest amongst a Spaniard noble population that agreed with De Las Casas, and a compromise could’ve been reached to prevent the reinstallation of the encomienda system. Reinstallation, because he actually had nominally succeeded in passing laws to prevent the abuse of the natives.

In 1542, he was successful in getting the “New Laws” passed, which stipulated better treatment of the native population. It wasn’t necessarily even ignored, the viceroyalty of New Spain (Central America today) essentially declined the King’s decree to end the system and treat natives better because so much wealth was being accrued from it, and the King wasn’t bound to the New Laws in the slightest, there was no tangible consequence for not following them besides the moral wrath of De Las Casas, a relatively irrelevant clergyman.

A dark example of this is the Nukes on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The argument for whether we should or should not have dropped the bombs is oftentimes extremely shallow. The US did not only nuke Japan twice, but they ran an entire air raid campaign to prepare for their land invasion from 1942 to 1945. Tokyo experienced the deadliest air raid of the war, killing around a hundred thousand civilians and leaving a million homeless. [12]

There is a very lively debate about whether the bombs were justified in ending the war. There is absolutely no room for any sort of moral indignation against those who advocate for the use of the nukes because the alternative could have been the continual and brutal firebombing of other Japanese cities, and an eventual land invasion of the mainland, through a plan called Operation Downfall, whose casualty estimates goes to the millions depending on how intense the resistance would have been.

The Japanese government was a military dictatorship, as the military branch of the government had essentially taken over control, whose entire legitimacy to power was the ability to wage war. Could they really be expected to surrender? It was also not an offensive war on behalf of the Americans, but rather a defensive war because the Japanese believed American involvement was inevitable and they wanted to buy some time by attacking Pearl Harbor

On the other hand, The nazis tried to bomb the UK during the war to lower their morale and force them to peace out of the war, but this didn’t work at all, and some argue that it only boosted British morale in fighting the war. The nukes could’ve just strengthened Japanese resolve especially if the government propaganda was good enough on behalf of the government, but they were on their last legs, and their eventual loss was obvious.

Politics tend to be very complicated and multifaceted. To take a blind moral axe to a conversation is a total waste of time for everyone involved. It doesn’t get anyone anywhere.

The progressives of the US would benefit from a Machiavellian method to go about their accruement of power, so as to bring in their progressive policies. If morality is an expression of a particular power structure, then it does not matter if one feels that I am on the right side of history! Which overwhelmingly seems to be the feeling held by progressives across the world.

Las Casas’ failure, despite his high moral standing, permitted the continued enslavement of the native populations of the new world and the transatlantic slave trade to support the colonies because his means were inadequate for his admirable goals. The natives do not care if Las Casas dresses up his argument well, they would probably rather he get it done in whatever way possible because of the personal investment in the matter, that is, their enslavement and torture.

If a civil war broke out in Spain due to unrest caused by De Las Casas, and he won and actually changed the treatment and moral understanding of the natives, we would memorialize it as an important turn in human rights, despite the deaths of the military population, many of them who would be completely uninvolved in the style of colonization set by the encomienda system as they live on the Spanish mainland.

At the same time, we have to consider respect for the institutions and the meaning they provide. As nice as it would’ve been for Las Casas to use more intense power plays to prevent the enslavement of the native population, it is possible that his moves would undermine the government in such a way that it would leave it up to chance what will happen to the populations of the new world.

Dictators tend to rise up during times of instability. Hitler because of the many problems of the Weimar Republic, Napoleon because of the French Revolution, and Castro because of the corruption leading to the revolution in Cuba.

Trust in the government works in the same way that trust and belief in religion work. Just in the same way that interpersonal trust prevents bad circumstances of peer pressure, a reliable network of cause and effect allows for one to make choices and expect them to be fulfilled. If the government does not enforce the laws, then the laws are pointless, as was the case with the 1542 new laws which the emperor of Spain nor the viceroyalty of new spain cared for, and while no one cared for natives then, this willful ignorance of the law will inevitably lead to revolt amongst more powerful populations.

For a historical detour and example…

Republican Rome, shortly before Julius Caesar took dictatorial control over the republic, was extremely unstable and the power balance was shifting to the generals who held the Legions. Despite Caesar strong-arming the republic to respect his power, he was assassinated.

His adopted son, Octavian, later Caesar Augustus, gathered his power through tactful power moves. Whereas Caesar would have pardoned his opponents in the civil war – thus humiliating them in a Roman context – Augustus made himself the “first among equals” by naming himself princeps civitatis, literally the first citizen, who in the Roman Senate would be the first to speak to the senate gathering about the bill or issue at hand.

He gave his opinions first, and then through a general understanding that you could not really disagree with Augustus, as the richest man in Rome, restorer of the republic, son of Julius Caesar, and so on, everyone would follow and agree with whatever his response was. He also flooded the Senate with partisans when he first took power who would not object to him, making it harder to even gather a minority large enough to oppose his decisions.

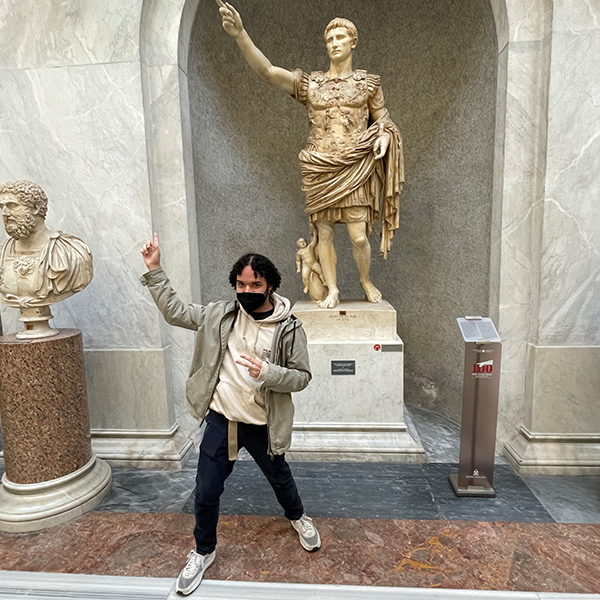

He also made great efforts with his propaganda and aggrandizing himself. There is the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, the Deeds of the Divine Augustus, which was written and spread across the empire, from Spain to Egypt. It is an embellished retelling of how Augustus managed to bring peace to the republic. Another is this statue of Augustus. It is rich in symbolism the Romans would have understood, but otherwise to us he looks powerful and nice enough to have a baby hanging from his leg. There is also me in front, being brainwashed by the propaganda in real-time when I visited Rome and made one of my goals to go see this statue.

At the same time, he effectively ended the republican model that we admire today at the very least in its ideal of being nominally republican and thus closer to democratic than not. He was also a dictator, and all the negative moral implications of that position are very much present here and possibly even worse by our moral standards today.

Here’s a quote from Russell: “The question is ultimately one of power. To achieve a political end, power, of one kind or another, is necessary. This plain fact is concealed by slogans, such as ‘right will prevail’ or ‘the triumph of evil is short-lived.’ If the side that you think right prevails, that is because it has superior power.”[13] What Augustus did bring, however, was unprecedented peace within the borders of the entire empire and a belief that his form of government was preferable to the instability of the republic.

At the time, following several civil wars which the Roman public had become exhausted with, their moral attitude towards the republic deteriorated and shifted towards whatever it was that brought some peace, which was the Augustan principate model under which the Roman emperor would speak first, have command over the legions, was the religious head of state and all of the other powers which Augustus collected granted to himself under this new position by simply holding these offices indefinitely or making it clear that they had no power over and above his command.

Even though Augustus made overtures during his lifetime and created this model of pretending to care about the senate, it was generally understood that Rome was a republic only in name following Caesar’s civil war.

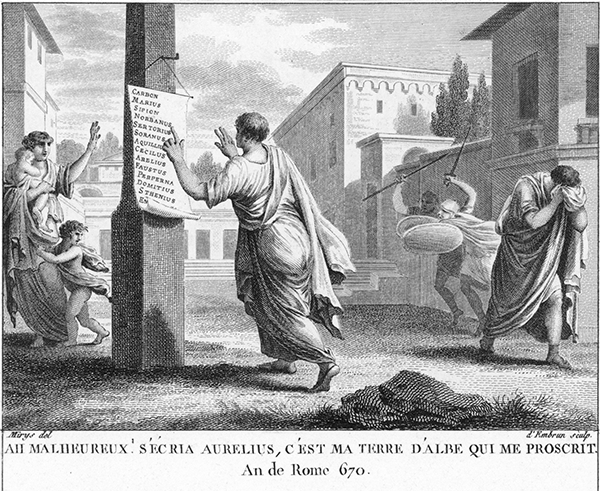

Julius Caesar himself came to power because of the institutions being undermined, he directly experienced the effects of an unstable government because of the dictatorship of Sulla, who won a civil war and proscribed – put on a list to be executed – his political opponents, including Caesar, who paid the bribe to escape the execution and likely held that terror for the rest of his life, perhaps a reason for why he chose to pardon his opponents in a civil war that he started rather than executing them and avoiding the headache later on.

Effective politics is a careful play at the edges of the dogmatism presented by the society, pushing these edges towards our desires, and hoping eventually the general societal belief shifts with the change in policy. Despite the Romans having a culturally significant disgust of kings after they overthrew them in 509 BC, the principate model bridged the cultural disdain and eventually shifted it when Diocletian, around 300 years later, would simply be referred to as Lord (dominus), a practice that was actively discouraged during the earlier principate period because it made people nervous about Rome becoming a kingdom again.

Concluding remarks

Despite the general attitude that Machiavelli (yes, this was an article about Machiavelli) held towards politics, his actual written advice for rulers is not very usable today and was very shallow at the time: “Machiavelli’s political thinking, like that of most of the ancients, is one respect somewhat shallow. He is occupied with the great lawgivers, such as Lycurgus and Solon, who are supposed to create a community all in one piece, with little regard to what has gone before.”[14] Machiavelli’s analysis was also very contemporaneous, it followed the idea that you would have a singular ruler who would decree laws and hold power.

The Italian states of the time had a similar dynamic to that of ancient Greeks’ Polis, or city-states, which Aristotle similarly wrote politics for since it had existed since around 700 BCE, which became entirely irrelevant as his own student Alexander the Great conquered his way to destroying the independence of the small city-states and uniting them under one empire beginning in 334 BCE after which all of Aristotle’s ideas on politics would be pointless for the circumstance.

An effective government and people work in unison to create something both agree upon. If the people are invested and the government is invested in its success, then it will likely succeed. A governor ruling using fear, admiration, wealth, and fame, individually will not get far in governing, but in unison can work quite well. If you can manage to convince a population that what you want is in their interest as well, then they will do it for you willingly. This is the idea behind propaganda. There is less resistance if they genuinely believe what is being said.

Personal relationships work much in the same way. How do people in relationships maintain power? Ambiguity, confusion, obfuscation, undeniable requests, and so on.

Thanks for reading!

[1] Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy, A Touchstone Book (New York u.a: Simon and Schuster, 1972). (p. 504)

[2] “Definition of HUMBUG,” accessed June 29, 2023, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/humbug.

[3] Russell, A History of Western Philosophy. (p. 504)

[4] Russell. (p. 505)

[5] “Girolamo Savonarola,” in Wikipedia, June 25, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Girolamo_Savonarola&oldid=1161773225.

[6] Russell, A History of Western Philosophy. (p. 505)

[7] Russell. (p. 507)

[8] Russell. (p. 508)

[9] Russell. (p. 507)

[10] Russell. (p. 510)

[11] “Bartolomé de Las Casas,” in Wikipedia, June 28, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bartolom%C3%A9_de_las_Casas&oldid=1162294276.

[12] “March 9, 1945: Burning the Heart Out of the Enemy | WIRED,” accessed June 27, 2023, https://www.wired.com/2011/03/0309incendiary-bombs-kill-100000-tokyo/.

[13] Russell. (p. 510)

[14] Russell. (p. 511)