Last time we left on a discussion of Machiavelli, a man from Florence whose political ideas were so great, he is often called the father of modern political philosophy, for the separation of morality from politics, one of many ideas.

From a little bit of searching though, I also see that modern is debated as a label for Machiavelli because he comes up with novel solutions for old problems, not based on dogma or scholasticism (meaning the church) but paid too much attention to preexisting traditions which held back his thought from being truly innovative.[1]

This is the nature of the Renaissance, before original thought could start to appear, the readers of those times had to go through all the new texts pouring in from the East, lost to Western Europe for centuries.

Anyways, this week we have Erasmus and More, who come as a pair in the chapter, neither of which are philosophers. Russell says we speak of them because: “[…] they illustrate the temper of a pre-revolutionary age, when there is a widespread demand for moderate reform, and timid men have not yet been frightened into reaction by extremists.”[2]

I am neither historian nor theologian, but here is what I understand: Europe during the early 16th and late 15th century was closing out the medieval era or the Middle Ages. The system of European governance across the different states of the time varied, but an incredibly important source of stability was food and population.

Let’s do a little catch-up on history, as far as I understand it.

The reason why Christianity became so widespread during the Roman period was because it was more desirable to the soldiers and people of Rome, whose empire was going through an extended collapse from 235 to 284.

While the cults of Rome did not provide comfort or good auspices, or signs of the future, the empire had collapsed under those beliefs. On the other hand, Christianity offered salvation to all of those who followed the word of Christ.

The ease of entry to the religion made it appealing as well since you did not have to be a specific kind of person to be a proper Christian. Saint Augustine around 400 solidified this belief, who claimed that eternal salvation was possible in heaven and that temporal events did not affect the eternal plane, where people went if they are good, supposedly.[3]

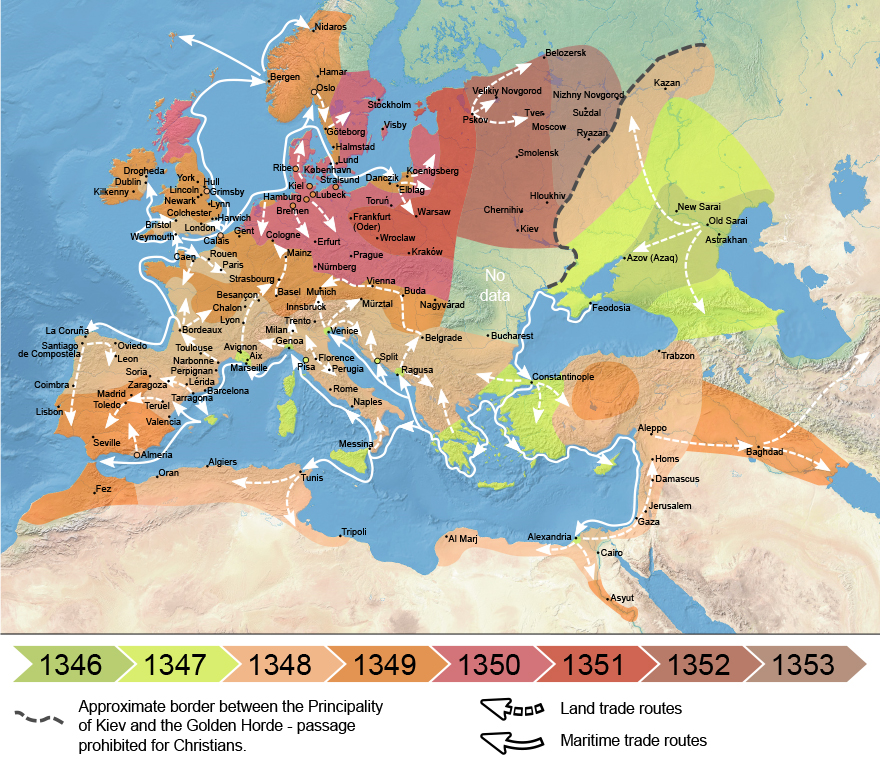

The belief in salvation and the stability brought by the church can only work for so long though before it starts to seem dubious in the face of other crises. There was a great famine from 1315-1317 where 5-12% of the population of northern Europe died, and then the plague just 40 years later, the black death, where 75-200 million people died, amounting to 30-60% of the European population.

If believing in God is supposed to stop earth-ending catastrophes, what happened? This was one of many catalysts for the protestant reformation, where Martin Luther would point to acts like the selling of indulgences as the reason for God abandoning Earth. Indulgences were literally, here’s a donation to the church, and now you are either partly absolved of sin or fully, depending on your pay and if you had already confessed to it at confessional, which didn’t make any sense, because repentance doesn’t make any sense when you pay for it.

Returning to Erasmus, while he enjoyed learning, he did not find any of the discussions at the time interesting, since the debates were old and tiring and nothing new was being developed. Colet, a humanist, and theologian, “lectured on the bible without knowing Greek; Erasmus, feeling that he would like to do work on the bible, considered that a knowledge of Greek was essential […] he determined to edit Saint Jerome and to bring out a Greek Testament with a new Latin translation; both were achieved in 1516. The discovery of inaccuracies in the Vulgate was subsequently of use to the protestants in controversy.”[4]

The Latin bible also known as the Vulgate, put together by Jerome and begun in 382 was the bible for the catholic church for more than a thousand years, replaced by the Douai-Rheins in 1582. The Kings Bible, published in 1611, was the protestant English version of the bible, which fixed a lot of inaccuracies in the original translation, but was separate from the Catholic bible. [5]

For most of the history of the church, Latin mass was done in Latin, up until the second Vatican Council in the 1960s. Quite literally, the preacher would read the bible in Latin, and then interpret it for the people who were listening to a language they could not understand. So, they could have whatever interpretation, and people would nod along. For the most part, it probably wasn’t so bad, but it gave the church and corrupt clergymen a lot of room to interpret the bible however they wanted since nobody would object.

I see the distancing between the protestants and the Catholics as being a result of the renewed interest in reading classics, thereby being able to read the bible in one of the original translations, the Greek testaments in Koine Greek, alongside other abuses by the clergy and the pope.

Which finally gives me the opportunity to go on a tangent about reading in the modern era. I write about the importance of reading for many reasons including our sanity in my undergraduate thesis, but the point here is that reading and therefore having to hold each subsequent word in one’s mind in conjunction is different from hearing words being spoken. While they are very similar, the skillset that we use is different in both.

After reading a journal article by A.K. Gavrilov called Techniques of Reading in Classical Antiquity I found that it was actually a myth for the people of antiquity to always read aloud. It seems to be that for the ancient romans, they didn’t have spaces in their words, so it was harder to read. Some have suggested that it was rare for people in antiquity to read silently because it would be difficult to read without spaces, although that theory seems to appear from a misinterpretation of Augustine’s view of Ambrose amongst other sources; Ambrose reading in silence was him being more spiritual, faster, and more focused but also that it was at the expense of his fellow religious companions that they were deprived of his knowledge. This notion comes to us because of the religious idea that withdrawal from the physical world indicates a connection closer to the spiritual which reading aloud would not serve, since it aims to please people who can hear.

The misinterpretation comes from the idea that Augustine was distraught at Ambrose for not reading aloud for his own spiritual journey, since he would’ve liked to hear what Ambrose thought. In the context of religious reading, one would expect for the reading to be done aloud, so Augustine found it odd that in this context he read silently, not that all silent reading was odd, since it was probably done regularly.

This article also brings up the modern notion of eye-voice span, that a person who reads aloud needs to be able to read ahead internally to understand the proper intonation and mood of what is being read in order to produce the correct voicing of the text, which is a skill trained particularly when having to read aloud. Thus, training this skill would be important in a culture which places importance on reading. You can also say that it works in the other direction as well. If you are reading by yourself and you understand the proper intonation and energy when reading in silence, you will have a greater connection and greater understanding of the text.[6]

Nowadays, people don’t tend to read very well. Apologies to those who struggle to read aloud at a good pace without stumbling, but this was an issue present throughout all of school, up to and including college. I have seen countless arguments and had countless arguments where the person didn’t read the whole text and drew conclusions before it was appropriate to do so.

Even reading silently when they go through the effort of reading the whole, they are unable to discern whether what is written is a good proper logical argument or if it is just an appeal to emotion. Both are important, but the rhetorical attempt can only come after the logical attempt to explain, particularly for those who are not as keen to pick up and integrate the logical argument into their understanding of the world.

Which is all to say – please read more. It will enhance your understanding of all aspects of life, being able to pick up on more of what is happening in what you watch, what you listen to, what you read online. It doesn’t matter what you read, if you read it in full and earnestly.

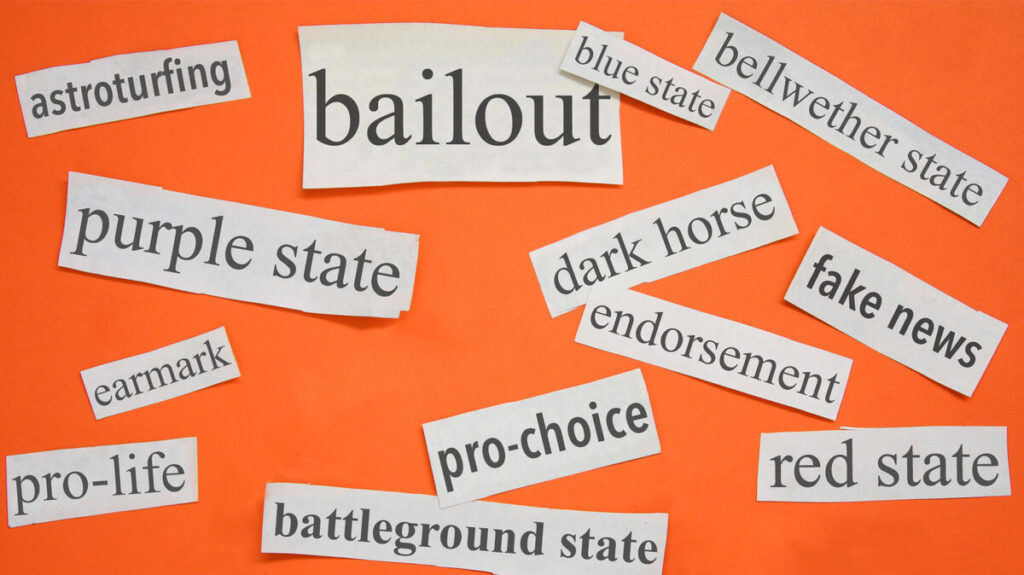

Twitter, for example, is a cancer on people’s ability to read critically. To form proper arguments in such a short span is nearly impossible, and it should really only be considered a dishonest attempt to convince you of something that you probably ought not believe, since a good argument will not be written in however many characters Twitter allows today.

Impact words dominate our communication nowadays, which are most dominant in similarly short readings where these impact words are used that imply a certain way of thinking that doesn’t allow any difference in thinking, or any new developments. In American politics, socialism is almost a forbidden word amongst democrats, because the Center base will always be disdainful at the sound of the word and will tune out everything else that is said following it.

As the world changes, we need to be able to change our understanding of the world as well, lest we allow foreign sources to influence our way of thinking. These foreign sources don’t have your interests in mind, creating a properly informed reader, but rather a slightly informed reader who cannot develop his own ideas and think whether what they read was true or not, in the same fashion that an unskilled reader will not be able to voice properly what they are reading and thus extract the proper emotions of what is being written.

I wonder sometimes what people think about when they read. I have sometimes read books where it is exceedingly difficult for me to form an idea of what is being written about because not enough is being described for me to form an idea of where to situate myself as a reader. Writing as a form has become most important in the form of film, where writing is arguably most profitable for a publisher, compared to a traditional book. Writing for films explicitly considers the location and feeling of what is being written about, but outside of the listeners purview, it will be in the directors’ hand to decide what looks like what and it becomes a visual task.

When this becomes the case, it is hard to develop any other idea by yourself. Have you read a book and then it was adapted to film? I think of the Giver, which is meant to be a utopia or dystopia depending on how you look at it, where no one can read anything from the past, and people are assigned jobs and only one person is assigned the role of reading the past, and therefore all the pain and suffering in order to avoid it for this society. The book itself may be interpreted and read and imagined to be a very positive sort of world, right up until the main character meets the giver, but from the way the film is directed, you can sort of tell that something is already wrong with the world as it is.

The movie is shot in black and white until the main character can rediscover color – which is a fine directorial choice – but it also removes the agency from the reader to imagine the world in color, to see the dystopia written as such as something positive in the film, which is a plausible view. The characters of the world are relatively content, if I remember correctly. The main character does not know he is supposed to see color, but we certainly do, and we wonder why the film isn’t in color rather than imagining a world on our own which might or might not be in color. So, it presupposes the dystopian setting rather than letting us believe it.

So go and read some more, become more imaginative, fill your own world with color and work on your ability to interpret, as this will enhance your view of the world, what seems right or wrong to you, and not what is given to you as a byproduct of the film experience, and in general, what is given to you through impact words and short headlines.

As a smaller side note on this: google scholar is free, for the most part. A lot of articles on a lot of questions you have are already available, and they tend to be very well written to allow people to read them.

Erasmus has one book which is read, according to Russell, The Praise of Folly. He summarizes the points of the book as follows: “Who can be happy without flattery or without self-love? Yet such happiness is folly. The happiest men are those who are nearest the brutes and divest themselves of reason. The best happiness is that which is based on delusion, since it costs least: it is easier to imagine oneself a king than to make oneself a king in reality. Erasmus proceeds to make fun of national pride and professional conceit: almost all professors of the arts and sciences are egregiously conceited, and derive their happiness from their conceit.”[7]

I find this line of thought interesting, since it seems to be the case that people have taken pride in their abilities to do rather than their general existence and their actual living in the world, which I find to be much more compelling for a source of happiness, especially in our times, when we are exposed to the entire world of people and abilities, where you can always find someone who does everything better than you do.

You really cannot be the best person in the world at anything, so why care about whether you are or not. I am a very competitive person, I become very passionate when I am embroiled in a challenge with someone else, but I try my best to not let this dominate my mental wellbeing nor have I let it be the source of my happiness.

As to national pride: I found this one even more bizarre. I didn’t do anything at all to be born where I was, nor where I was raised. I was born in the Dominican Republic and then I moved to New York City when I was young, am I meant to be proud of my New York culture or my Dominican culture?

This is especially true when we consider that the national pride of certain people is heavily derided, and often denounced as backwards.

I take great joy instead in the specific Dominican dialect, and the Spanish language in general. It is so colorful and has in my opinion, from my very small native ability to speak it, so much more versatility in expressiveness and fun phrases. Maybe I am blind to these in English because it is my dominant language, and it tends to be that the dominant language simply blends into our consciousness, and we have a hard time thinking of it critically. I could also be romanticizing Spanish since I don’t know the full extent of it.

To put it shortly, Spanish has a formal case and a non-formal case, where I can address a person in a more polite manner and in a more friendly manner. The more polite manner, I find, sounds so much more diplomatic and interesting to listen to because it has obvious care for the status of the person you are speaking to. It is still a bit hierarchical in thought since you refer to your elders in the formal, nonetheless, it’s a beautiful expression of respect for those you wish to respect, a choice in the manner with which you address someone.

What do we make of the other part of that quote? That it is better to imagine oneself as a king rather than being an actual king? I don’t know about that in particular, but I like to do what I like to do, and I try to avoid thinking about what other people think about on what I like doing, and that generally seems to work for me. Happiness is a very complicated set of circumstances, I may enjoy doing X Y, and Z, but for my enjoyment to be true, I may need A B and C to be settled for me to enjoy the former. A B and C may be shelter, food, and safety.

Here’s a personal example. During my last year as a college student, I had a hard time enjoying videogames because I had the impending doom of my thesis in the back of my head.

I had an extended lapse of judgment throughout my senior year. I signed up for a yearlong thesis, and I spent the first half of that year, the first semester, doing absolutely nothing. I think at most I read 20 or so pages from a book I don’t think I used at all. Despite not doing anything, I was very stressed out at the concept of me not doing anything, and I couldn’t help but think about that during the times that I set aside to relax and play videogames or watch TV thus ruining my enjoyment and happiness.

You can also say that the quote means to be blissfully blind in your knowledge of the world. Some people worry a lot about the state of climate change, and it seems that every summer we are shocked to see the latest heatwaves, and every winter every weird wave of cold. If you have a hard time grasping the consequences of climate change or are willingly avoiding the issue, you may be content about the state of your current and future safety in that way as well.

Moving on, Monastic Orders. The entry foray into any history enthusiast for guys – the Knights Templar, Teutonic Order, Livonian Order, Knights of Malta, and so many many more. These were the guys leading the charge… into protecting Christians doing a pilgrimage and defending the carve-outs from the occasionally successful crusade into the middle east.

The northern crusades, in and around the Baltics, were leading a charge to conquer land from non-Christians, for arable land and serfs and trade routes. Aside from being military orders, they were supposedly very religious, they had their routines, and ways of showing devotion, that Erasmus critiques as being “‘brainsick fools,’ who have very little religion in them, yet are ‘highly in love with themselves, and fond admirers of their own happiness.’”[8] Similarly, he critiques priests for ecclesiastical abuses: “Pardons and indulgences, by which priests ‘compute the time of each soul’s residence in purgatory.’”[9]

What he suggests instead as proper religiosity is in the form of folly. Russell summarizes: “There are, throughout, two kinds of Folly, one praised ironically, the other seriously, the kind praised seriously is displayed in Christian simplicity.” In which, “true religion comes from the heart, not the head, and all elaborate theology is superfluous.”[10]

Happiness may also come in the flavor of religion. There is no need to worry about climate change per se if you are religious and expect God to do well by you and your faithfulness and protect you from the oncoming catastrophe. I’m sure that this nice consideration god extends to you also comes only with respecting the earth properly and not allowing climate change and your impact to go beyond and harming other people, so it isn’t necessarily an excuse to pollute more, but rather to put the comfort of the end of the world in the hands of god and hope he has something nicer in mind.

Given the overly rational world state we are in right now, where everything needs a justification and a reason to do, I do believe that those rituals which Erasmus critiques are more important today than they were in his time. It might have been easier to believe in a sky woman or man when we didn’t know the causal reason for half of the things we saw in the world. Science had not developed and become dominant as much as it has today.

Rituals, like for example, that of burial, are something that creates a feeling of community within a group of people, an expectation for good acting so that when you die, you are treated with respect. Religious gatherings like mass, for example, are a collective belief in the existence of God, eating those thin pieces of bread that they give you to eat and be closer to Christ, and so on.

Doing these kinds of activities repeatedly has some value today in making us feel the existence of God. I am an atheist at most and agnostic if pushed, but I don’t deny the importance of religion for most people. It brings great comfort and order into a world that is increasingly becoming hostile to fostering a feeling of happiness for us.

Erasmus mentions something else of note: “Plato should be studied, but not the subjects which Plato thought worth studying.”[11] People of different ages will always use different thought processes and sets of ideas to reach where they are in their mode of thinking. Plato is a valuable thinker, not in what he has to say about any of the metaphysics of the world, but in the way that he was able to get to those ideas.

He has a form of thinking which is timeless in reaching conclusions, and although they can be critiqued deeply, keep in mind that his way of thinking in Christendom was maintained in the form of Neo-Platonism and its combination with Christian philosophy until Aristotle was rediscovered in the 12th century. who, by the way, had a form of thinking which still haunts us today, particularly in the conception of many fields of study. We should read Plato and Aristotle because they are the foundational pieces of rational thought for the society we live in today, and seeing through their explanations should help us understand how other people come to reason the beliefs they hold today.

Erasmus’ interest in the world came from reading the old classics, and anything else that he came upon. That is the source of the Renaissance, a rebirth of the study of the ancients, which eventually ran out. There was only so much to read before they had to develop their own ways of thinking, and so “the curiosity of the Renaissance, from having been literary, gradually become scientific.”[12]

There were developments in learning in some capacity in the Middle Ages, and as the ancients were rediscovered and read, it was also clear that they were wrong in many aspects. New thinking had to stem from this, and so they did. Hopefully, we are almost around the corner in dealing with religious issues in this book and onto different philosophies, philosophy still studies the idea of God, but not in the ‘sky person watching over our way.’

Erasmus’ other work was a book to teach Latin, “He wrote an immensely successful book of colloquies, to teach people how to talk in Latin about every-day matters, such as a game of bowls. This was, perhaps, more useful than it seems now. Latin was the only international language, and students at the University of Paris came from all over Western Europe. It may have often happened that Latin was the only language in which two students could converse.”[13]

While Latin may not be relevant today, English certainly is. I believe English should be taught as a secondary language in every single school across the world. Like Latin, it may be the language that two different peoples may use to communicate – a Portuguese person and a Japanese person would probably speak to one another in English in a business context, rather than both speaking one of each other’s languages. I choose English simply because it has already been established as the business language; any other language would do, but this one is already in place. It is also the dominant language of the internet.

Different languages have different emotional expectations, which is the one of the troubles in making English the standard language for all. For example, a base greeting, “it’s nice to meet you” is a blanket statement of greeting, it might as well be comparable to hello, but it introduces a faux politeness in the English language that is an extra expression of the ways that English people are expected to act with one another.

In British English, it constantly sounds like they are being overly polite while simultaneously hating each other. In German, the verb can go at the end of the sentence given that a modal verb is used at the beginning of the sentence, so when listening it can be confusing to understand what the purpose of the sentence is until we reach the end of it. This is not the case in English.

Grammatical structures imply a certain way of being, and by saying that English should be taught, I also say that we should conform to one way of being. I understand the trouble of this, but I also sympathize with the trouble of all of those non-English speakers, to which the internet is half not catered to them, and where if they happen to move to the United States, such as my parents did, not having learned English could mean a serious decline in the quality of life and opportunity of that person. This means much more to me than worrying about cultural imperialism which I would hope would stay relatively neutered, as it would be the second language taught, not necessarily the native one. With that, we end our reading of Erasmus and move on to More.

Let us keep his historical section short: in essence, he became a chancellor for the king of England, which unluckily for him was Henry VIII, the one who killed his wives. More objected to the divorce of Catherine of Aragon for Anne Boleyn and resigned for this dissent. This was in 1532. In 1534 the King passed an act which made him the head of the church, which therefore separated the English church from the Catholics. With this came a requirement that all important people in England agreed that this was the case, and on dubious testimony, More was said to have said that Henry could not ask parliament to make him the head of the church and was subsequently convicted of high treason and executed.

He wrote a book, Utopia, in which “all things are held in common, for the public good cannot flourish where there is private property, and without communism there can be no equality. More, in the dialogue, objects that communism would make men idle, and destroy respect for magistrates; to this Raphael replies that no one would say this who had lived in utopia.”[14]

The book is written in a dialogue format, meaning that More, the author, is meeting a person who traveled to the city of Utopia, fictional, of course, and traveled back to England to tell More all about it. In the city, everything is identical, people work a set number of hours, all people work, all people wear the same clothes, all people do the same thing, if there is a surplus then the bureaucrats announce a shorter working day. There are some weird family dynamics that he describes as well, essentially patriarchal. To the point of war, they only do so “to defend their territory when invaded; to deliver the territory of an ally from invaders; and to free an oppressed nation from tyranny.”[15]

I find the last point particularly interesting, since rule under a tyranny can really mean a wide variety of things and can be the justification for wars that seem rather motivated by other reasons. For example, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is under the pretense of liberating a part of Ukraine for Russians who are not happy with the state of the government in Ukraine and therefore to form a separate state, which, ironically happens to stem from Russian propaganda and also the fact that during the time of the Russian empire and into the period of the soviets, there was an overt colonization and ethnic cleansing effort by Russians in Ukrainian lands, before Ukraine gained their independence.

Even the loveliest of Utopias, as described by More, has odd inclusions for the oversight of the sovereignty of another people. You can take this positively, as a care for the well being of people across the world. The end of the book has Raphael, the visitor of Utopia, spreading Christianity which shortly becomes the standard religion for the city thus possibly being an imperialistic interest to guarantee some interests from other countries and bring Utopia under the Catholic Church, which is supposed to have nominal control over every country which follows it. It could also mean changing the government form to one like that of Utopia’s to guarantee the end of invasions, or a puppet state which remains in control of the government of utopia.

The importance of Christianity being spread was to introduce the notion of private property being extra bad, since the Utopians already believed this was the case, it was easy for them to convert to Christianity, and a lot of stress is placed on this notion. I quote “we are told that in all other nations ‘I can perceive nothing but a certain conspiracy of rich men procuring their own commodities under the name and title of the common wealth.’”[16]

With that, we conclude the reading of Erasmus and More. To say something about Russell, and a valuable point that he brought up, he says: “It must be admitted, however, that life in More’s Utopia, as in most others, would be intolerably dull. Diversity is essential to happiness, and in Utopia there is hardly any. This is a defect of all planned social systems, actual as well as imaginary.”[17] I happen to agree with Russell, but only incidentally.

I think it is the case that life would be a bore in these societies, but only because the stratified nature of our society affords us with pleasures that are beyond what is ethically reasonable. We enjoy products at such a low cost compared to the human expense needed to make them, that it is questionable whether we should be enjoying them. At the cheapness of our products comes climate change, and it is a question about slowing down this massive hurling comet coming towards the well being of our earth. Maybe we are too happy and we enjoy too much, to the extent that we are burning ourselves out. I’m sure it would be intolerably dull, but it calls to questions what our life is like today rather than that society being too boring.

Keep in mind that as I read this book, Russell’s 20th century presuppositions, such as the conflict between democracy and communism will grip his way of viewing things, and I will try as much as possible to separate this reasoning from what he writes, but at the same time, what he chooses to summarize and include and not include is not in my control.

With that, this weeks commentary ends, which is followed by a very short chapter on The Reformation and Counter Reformation. Maybe I will skip this chapter, I haven’t decided yet. But for now, that will be next week’s chapter. If you’re listening, scroll to the bottom and leave a comment!

[1] Nederman, “Niccolò Machiavelli.”

[2] Russell, A History of Western Philosophy. (pp. 512)

[3] Brooks, “Reading.”

[4] Russell, A History of Western Philosophy. (514).

[5] “Summary Descriptions of Versions of the Bible.”

[6] Gavrilov, “Techniques of Reading in Classical Antiquity.”

[7] Russell, A History of Western Philosophy. (pp. 514)

[8] Russell. (p. 515)

[9] Russell. (p. 514)

[10] Russell. (pp. 515-516).

[11] Russell. (p. 516)

[12] Russell. (p. 516).

[13] Russell. (p. 517)

[14] Russell. (p. 519).

[15] Russell. (p. 520).

[16] Russell. (p. 521).

[17] Russell. (p. 522)